100 Years of Home Buying: Comparing 1920s Real Estate Listings to Today’s

It’s officially the ’20s again, and we’re throwing it back to the Roaring 1920s all week. Whether you love Jazz Age decor, historic homes, or just learning how people lived 100 years ago, we’ve got you covered. Cheers, old chap!

Our house was built in 1920, and it’s funny to think that the people who bought it a century ago probably took some of the same steps we did—even if they were buying a brand-new house rather than a battered old fixer-upper. They likely used a real estate agent, were probably just as enamored by the fireplace and convenient location in Quincy, Mass., and maybe even took out a loan to afford such a major purchase.

But the home-buying process wasn’t a carbon copy of today’s by a long shot.

“Many of the safeguards and processes that we take for granted today didn’t exist in the 1920s housing market,” says Frederik Heller, director of library services for the National Association of Realtors.

There was no such thing as a 30-year mortgage, for example, until after the Federal Housing Administration came about in 1934. There were no laws requiring the disclosure of structural issues or other known problems in a house, and buyers generally didn’t have anyone representing them.

“Sellers were represented by a broker, but there were no buyer’s agents the way there are now,” Heller said. “In fact, at the beginning of the 1920s, it would have been possible for your real estate broker, insurance agent, appraiser, mortgage lender, even the person who built your house, to all be the same person.”

All of this—the stuff that hasn’t changed at all, and the stuff that most definitely has—becomes pretty evident after taking a look at vintage real estate ads.

Real estate ads in the 1920s vs. 2020

One big difference between then and now is that there just aren’t a whole lot of real estate ads anymore—at least not in newspapers. With websites like Zillow and Redfin opening up access to the Multiple Listing Service (MLS), most people just head straight to the listings. Half of recent buyers found their home online, according to an NAR report, compared to 1 percent who found it in print.

“In the 1920s, the main venue for property listings was the classified section of the local newspaper—usually just two or three lines of text highlighting the key features, no photos,” Heller says. Bigger developments, like new subdivisions and apartment buildings, more closely resembled the remaining print ads we see today in newspapers or magazines, with photos and illustrations, he added.

Realty agencies couldn’t advertise every property, so the most important thing was to get their name out there and bring people into the office any way they could. The “for sale” signpost in front of a home was as crucial then as it is now. But no stone was left unturned: The very first paid commercial on radio was a 1922 ad for the Hawthorne Court Apartments in Queens, and one real estate office even distributed 20,000 branded rulers to local schools, figuring those same kids would be buying houses before long.

While the content and character of 1920s real estate listings seem remarkably familiar in some ways, and they’re very, very different in others. Ahead, find some of the similarities and differences between ads in the Boston Globe and New York Times archives from the 1920s.

Difference: Electricity and hot water were pretty big selling points

In 1920, only 1 percent of American homes had both electricity and indoor plumbing, though both were on their way to becoming mainstream. It wasn’t until 1925 that half of American homes were wired for electricity, and even in 1940, a third of U.S. homes still lacked a flush toilet. Such modern innovations, found mostly in cities at first, were worth pointing out to buyers.

A March 1920 ad in the Boston Globe advertised “an ideal house” at 17 Eustis Street in my neighborhood in Quincy—complete with “bath, toilets, steam heater,” and more. Other new features of the day have since either fallen out of fashion or faded into everyday life.

“In the 1920s, there are tons of ads for items such as ‘fireproof’ asbestos shingles, enameled plumbing fixtures, garbage incinerators—for both apartments and single-family homes—laminated flooring (‘withstands steam!’), ‘automatic’ gas water heaters, heated garages, refrigerators, and ironing boards that fold into the wall, among other features,” Heller says. “‘Door beds,’ or Murphy beds, seem to have been enormously popular, based on ads throughout the decade in the National Real Estate Journal,” he adds.

Similarity: Location, fireplaces, porches, and oak floors were all desirable features

Like many listings of the era, the ad for that Eustis Street house boasted that it was “desirably located” and outfitted with features like a sun parlor, fireplace, and oak floors. When the same property was sold in 2016, its location “in the heart of convenient Wollaston” still got top billing in its MLS listing. The enclosed porch, fireplace, and woodwork, all mentioned in 1920, were still big selling points a century later. In other listings, too many stairs were just as unpopular then as they are now: New York apartments with an elevator made sure to make mention of it.

In the 1920s many real estate listings bragged about how near a house was from the city or train station. Sound familiar? One 1925 ad boasts of a house “handy to cars, trains, and stores,” and a new development in Revere, Mass., (on “high, dry, healthful lots”) trumpets its location only ”two minutes to street cars, twenty-two minutes to Boston.” A brick two-family with a yard in Astoria, Queens, was only “15 minutes to Grand Central, 5c subway fare.”

Difference: Some real estate ads were overtly discriminatory

Some ads I came across from a century ago made reference to a home’s location in a “first-class American neighborhood” or in the “American section of town,” or used similar language to emphasize their position of privilege amid widespread and officially sanctioned segregation.

“Discrimination in listings is a huge difference between then and now,” Heller says. Sometimes it was blatantly obvious, but often it was more subtle, he says, using vague descriptions of location “‘on the north side of town,’ or ‘west of Maple Avenue,” for example, to indicate that the property was located in an area with few minorities or immigrants.

Of course, there is still discrimination in housing today, even after the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968 to protect renters, buyers, and mortgage-seekers from unfair treatment. More regulations have been put in place since the days of red-lining—real estate agents, for example, are not permitted to use the racially-loaded phrase “good schools” when marketing a property.

Difference: Build-your-own houses were advertised and sold through the Sears catalog

From 1908 to 1940, retail juggernaut and Amazon prequel Sears Roebuck & Co. sold build-your-own kit houses through their nearly ubiquitous catalog. The business hit its stride in the 1920s, as immigration soared and the country settled into a decade of prosperity after the end of World War I.

“We had a tremendous housing shortage, the war had just ended, and people truly believed there would be no more wars. It was a time of tremendous optimism and peace, and with that who doesn’t want a cute little house with a picket fence around it?” explains Rosemary Thornton, author of The Houses That Sears Built: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Sears Catalog Homes, when I spoke to her about Sears homes in 2017.

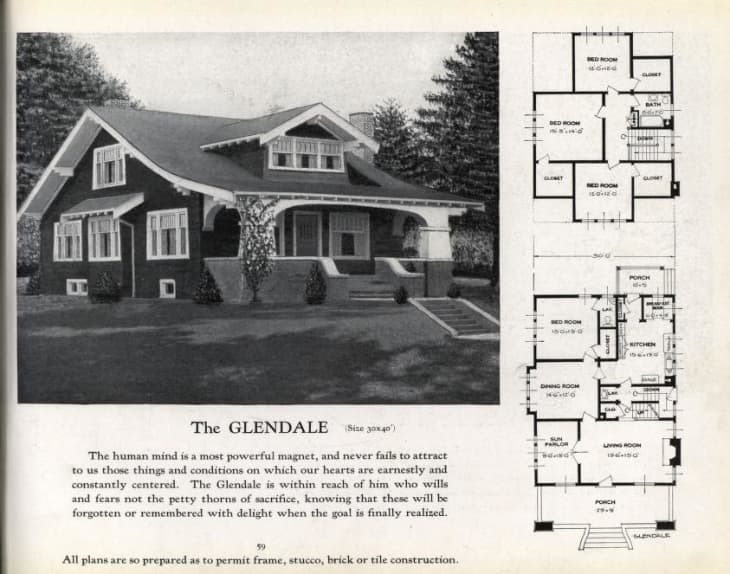

After selecting a style from the “Modern Homes” catalog (where one could browse floor plans, exterior drawings, and custom add-ons like plumbing) and ordering it by mail, your house would arrive via train: An assortment of some 30,000 parts, including about 750 pounds of nails, dozens of windows, thousands of shingles, and a 75-page, leather-bound instruction manual.

Sears offered refreshingly fair financing terms: If you owned a plot of land and you had a job, you could generally qualify for a mortgage, no matter your race, ethnicity, or gender. The do-it-yourself aspect helped thousands of ambitious homebuyers create instant equity and claim their slice of what was increasingly considered the American Dream.

“The view of home ownership was really changing in the popular mindset in the 1920s,” Heller said. “1920 was the first year that more people lived in urban areas than rural areas, the middle class was growing, and more people had the means to buy a home.”

Sears didn’t shut down its kit home business until 1940, but the 1920s were surely its heyday. “People who don’t know better say Sears stopped selling kit homes because of the Depression. That didn’t help things, but really housing just became increasingly complex” as electricity grew more commonplace, Thornton says. “If you were wired in 1925, you might have a single bulb hanging from a braided cord. If you needed to plug in a brand-new invention like a waffle iron, you’d unscrew the lightbulb and screw in an adapter to plug in your waffle maker,” she adds. By the end of the decade, electric service was far more sophisticated, and it was getting harder for amateurs to build a modern, wired home. Or as Thornton puts it, “Housing became very complicated very fast.”

Difference: 1920s houses were pretty darn small

The 1920s certainly saw the building of stately mansions and Gatsby-esque estates, but the average new home built that decade ranged from just 742 to 1,223 square feet. The average new home built in the third quarter of 2019, meanwhile, was more than double that size, at 2,464 square feet.

“The one style that was popular almost everywhere in the 1920s was the bungalow,” Heller says, which had spread across the country after debuting in the Los Angeles area in the early 1900s. “They were small, quick to build, affordable, and could be easily outfitted with the modern amenities that buyers were looking for, and they could be built relatively close together without creating a sense of overcrowding.”

Difference: Forget avocado toast. Cutting back on a few summer dresses could have gotten the Lost Generation a down payment

Looking through ads in 1920s newspapers, I couldn’t help but notice that apparel and furniture were surprisingly expensive. One could buy a house outside of Boston for about $6,500 in 1925 with a down payment as low as $500. Meanwhile, a four-piece bedroom set was advertised at $235, and summer dresses were on sale for $45 to $95 apiece. (Woolen knit bathing suits, on the other hand—yes, you read that correctly—were only $4.50 a pop that season.)

Paying $6,500 for a Boston-area house in 1925 would be equivalent to paying $96,551 today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator. That’s quite a bargain, given that the median price of a Massachusetts single-family house was $415,000 in December. But those $95 summer frocks would have cost the equivalent of $1,411 in today’s dollars. (FYI, the woolen bathing suit would run you $67 today.)

Similarity: Realtors were selling the affordable, attainable American Dream

What’s most striking to me is how our house’s inaugural buyers probably experienced the same sense of hope and excitement we did when buying their home almost a hundred years later. They were probably just trying to gain a foothold in this modern life, a place to make their own at a price they could handle.

“More than anything else, affordability was probably the ‘feature’ that was stressed the most in 1920s advertising,” Heller says. “The view of homeownership was shifting to become something anyone could or should strive for, so home builders and real estate brokers emphasized that in their ads: A convenient, modern home to call your own, with all of these features, and it only costs a few thousand dollars.”

Add a “hundred” in there and it’s not too far off.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clearly acknowledge the continuation of housing discrimination through the present day. We regret the oversight.