My Family Still Has a 100-Year-Old Houseplant — Here Are Our Best Plant Care Tips

In a back bedroom in a home in Fort Wayne, Indiana, there is a Christmas cactus (Schlumbergera truncata) that is at least 115 years old. When it’s not in bloom, it looks something like a dinosaur with hardened stems and scaly leaves. It’s in a pot that most people would classify as ginormous by houseplant standards and the soil remains dry and hard even after a thorough watering. But this plant has persevered through decades of both care and drought, still blooming each year during the holiday season.

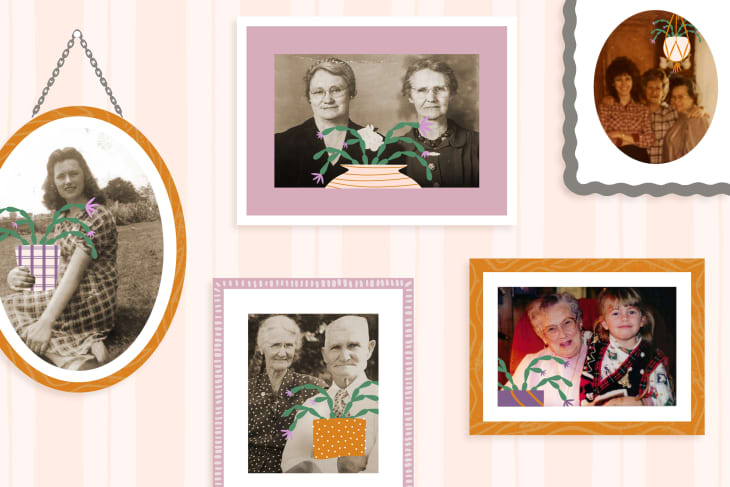

If you believe the Farmers’ Almanac, 30 years is over the hill for an indoor Christmas cactus — which makes this plant positively ancient. But it’s not just its age that makes it special (though being a centenarian does, of course, make it very special). This plant is one that I hold close to my heart. I come from a long line of professional and amateur plant fanatics, and this Christmas cactus is a line that connects us all. This plant has been passed down through four generations of my family, from my great-great-grandmother Anna Biven (Spence) English (1881-1958) to my great-grandmother Lucille (Fairweather) Melton (1904-1980); to my grandmother Mary Margaret (Melton) Gholson (1924-2015); and finally, to my second-cousin Larry Melton and his wife Shirley (1946-2018), who intend to pass it down to my mom, Nadine.

Family lore runs deep in this gene pool, mostly as a way to remember and honor those who came before us, and the legend of this particular plant was first told to me as a child. Back then, my mom would tell me about my great-grandmother Lucille’s massive plant collection that lived out in her enclosed back porch, how Lucille would brush the leaves of her African violets with baby doll brushes to clean them, and how she had a giant philodendron in the corner of the living room that climbed up and reached across the wall. Later, we found out that one of those plants — this Christmas cactus — actually belonged to Lucille’s mother Anna, predating everyone in the surviving family by decades.

This plant not only represents a history as a centennial piece of horticultural history — it is also a living piece of my ancestors that are no longer with us. In a sense, it’s a massive part of my family tree, living in a terracotta pot.

Last year I was chatting with my mom, Nadine — a professional flower farmer — about plants, and she mentioned great-grandma Lucille’s plant collection again. I asked her where all the plants had gone after she passed away. Evidently most of them had been spread to children and in-laws and had died off over the years. But one Christmas cactus — the Christmas cactus — had survived and was still in the care of my mom’s cousin Larry, 350 miles away in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

I balked. How could all of those plants have just disappeared with time? Here I was, parading myself around as a plant professional with a hereditary green thumb, but I knew so little about my great-grandmother’s collection — particularly this infamous Christmas cactus that was still living. After that, I had no choice. I had to know more.

Here’s what I found out: Lucille was a self-taught houseplant expert. She kept all kinds of philodendrons, African violets, and ferns on that back porch. At some point, though no one is quite sure when, her mother Anna’s Christmas cactus — probably bought between the early 1900s and the 1930s — joined the collection.

Garden centers and online greenhouses obviously didn’t exist in the early 20th century, and southern Illinois wasn’t exactly a booming metropolis back then, either. But the Victorian obsession with houseplants like ferns, palms, and Christmas cacti was strong, so there’s no doubt these curiosities were available for purchase. So wherever she got it, Anna kept her cactus thriving long enough to pass it on to her only child, Lucille.

Lucille doted on her plant collection almost as much as she doted on her grandchildren. In the winter, the Christmas cactus took up a warm corner of her enclosed back porch, but in the summer it got to live outside in the southern Illinois heat and humidity. Every summer it sat in the same spot, under the big shade tree in the backyard.

When Lucille died unexpectedly in 1980, my grandmother, Mary Margaret, became the caretaker for my great-grandfather Edo — and all of Lucille’s plants. It wasn’t long, though, until it became apparent that my grandmother had not inherited her mother’s green thumb. In fact, according to my mom, my grandma cared very little for keeping plants alive. When Lucille would visit her daughter’s house, the first order of business was to go around and water the few, sad plants that my grandma kept around. And then, suddenly, the non-plant-lover was tasked with keeping Lucille’s prized possessions alive.

Enter Larry and Shirley, my grandma’s nephew and wife from Fort Wayne, Indiana. My grandma was more than happy to hand over the Christmas cactus to them because, as she told Larry, “I’m probably killing it anyway.”

When Larry and Shirley decided to repot the plant, they realized that Mary Margaret was indeed slowly murdering it. It was planted in an old clay pot and completely rootbound to the point where only a small handful of mud-like soil remained at the bottom. Shirley repotted it and continued the care-taking tradition of keeping it safe and warm in the winter, and then moving it outside in the summer to live under a tree in their backyard. It was fertilized a few times a year and watered on a schedule for almost 40 years.

After Shirley passed away in 2018, Larry was left to his own devices to care for the Christmas cactus, which at that point was (at least) over a century old. For the last three years he’s watered it when he’s remembered to, and that’s just about it. And guess what? It’s doing just fine.

As I carried on this very personal research project, I sifted through hundreds of family photographs in search of physical evidence of great-grandma’s plant collection. There are hints. Like in the photo of my mom and her cousins on Easter Sunday. They’re dressed in their frilly best, posed on Lucille’s back porch. An African violet peeks from behind my mom’s skirt. In another, a series of relatives are posed in Lucille’s living room, where a long, spindly philodendron can be seen stretching up the wall. Photos of the Christmas cactus, however, are nowhere to be found. Perhaps because Lucille’s generation prized their relationships with people more than their relationships with things.

Larry, in his gracious spirit, has decided to pass the cactus down to my mom, who will eventually give it to me. It’s a surreal feeling to think that a living thing like a plant has lived through an entire century of world history. I mean, think about it! That Christmas cactus had lived through two world wars and the Great Depression before my mom was even born. That plant is older than air travel, antibiotics, and FM radio!

Wildly, caring for such an old plant isn’t as complicated as you’d think. But there are a few tips and tricks passed down through the years that keep this centurion plant thriving — and can help keep your plants with you for years to come, too.

Leave it alone.

Yes, really! You don’t want to crowd an established plant with too much attention. It’s doing its thing, and you should do yours. Don’t over-water, don’t get snip-happy, don’t re-pot frequently, and don’t constantly move it around. The most you should be doing on a regular basis is watering it and rotating it so the light exposure is equal on all sides of the plant.

But do give it some outside time.

If you have the outdoor space, put your plants outside when the weather gets warm. They will thank you! After all, plants do not exist to live permanently indoors. We modify our living spaces in hopes that our houseplants will find the environment desirable enough to at least stay alive. Treat your plant babies with a little outdoor time in the summer months.

If you don’t have outdoor space, just move your plants around once or twice a year. Even if it’s just a couple of feet, it will do them good.

Water in moderation.

In our family’s experience, underwatering is much easier to remedy than overwatering. You can always add more water, but you can’t take it away once the soil is saturated. This is especially true if you’re caring for arid desert plants like cacti and succulents. More often than not, your plant will tell you when it needs a drink, either by slightly drooping or shriveling a bit. The key here is to be an observant plant owner.

It’s hard to save roots once they’ve started to rot, so make sure that your plant is never sitting in too much moisture.

Repot every year.

Every year or two, you need to repot your plants. These are living things that grow out of their pots in the same way that children grow out of their clothes. Some plants like Christmas cacti, hoyas, and lipstick plants like to be rootbound, but there’s a difference between “happily snug” and “desperate for more space.” A too-tight fit means that roots can’t get the water and nutrients your plant needs to stay happy.

Repot in spring, when your plant will start to emerge from its sleepy winter state. And when you repot, size up your pot’s diameter by about one or two inches. Remember to choose something that has a drainage hole to avoid sitting water.

Fertilize in summer months.

Fertilizing is something that a lot of plant parents — myself included — can forget about. But do it! Fertilizing adds extra nutrients to the soil that promote growth and healthy roots.

Don’t fertilize in winter months, when your plants are taking a break from actively growing. And make sure you read the instructions and stick to the measurements — more is not better in this case. You can quickly kill off your entire collection of plants by over-fertilizing.

Appreciate your plant’s value.

I suppose this piece of advice is a little bit more emotional than logical, but hear me out. Every houseplant comes from somewhere — even if you buy it at the grocery store. Someone has germinated the seed, cared for it through infancy, and made sure that it’s healthy enough to put on a retail shelf. Someone cared for your plant before you brought it home. Remember that and cherish it. One day you might pass along your favorite plants to a loved one, and you’ll want them to care for your collection with as much dedication and affection as you did. Remember: it all starts with one plant and a story.