Flower Arranging Advice from the 1940s: “A Fascinating Hobby”

There’s never enough time given to understanding the past, and to how it’s shaped and influenced our thinking now. In “The Specimen Jar”, we’ll try to correct that deficiency by considering a variety of designers and their works, from many different periods. Because a beautiful and intelligently designed home is a living response to not just our own moment, but to history and to our hopes for the future.

***

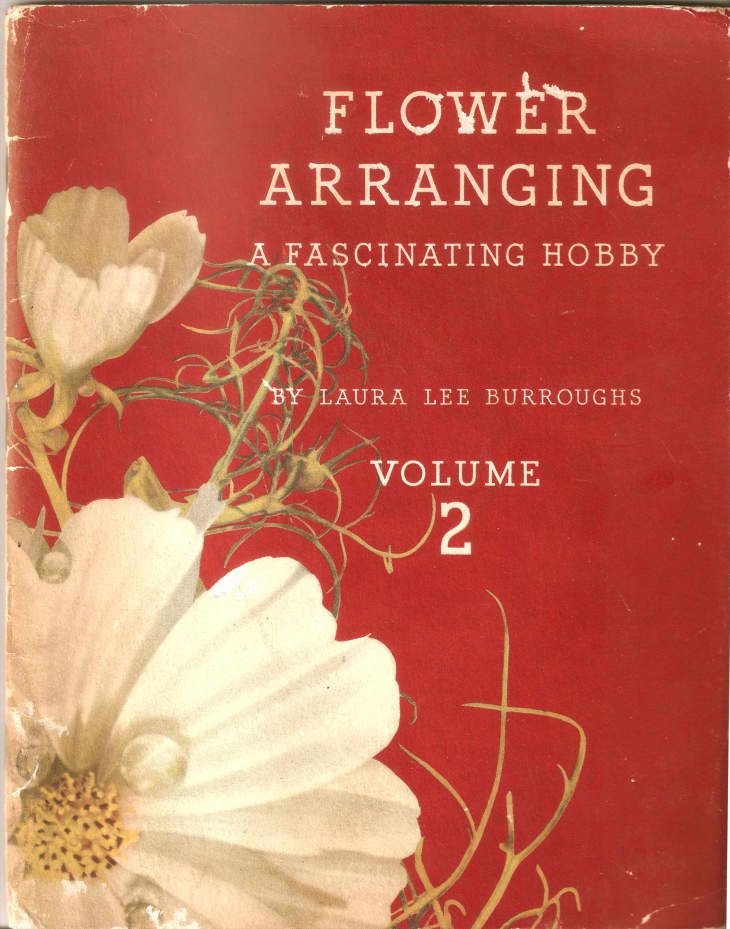

“We all like to have our homes admired,” observes Laura Lee Burroughs in the opening words of her 1941 booklet, Flower Arranging: A Fascinating Hobby (Vol. 2). “When friends visit our house or apartment, it is pleasant to have them enthusiastic about the excellent food, the original table decorations, and the attractive flower arrangements.”

Well, sure. Flowers! Even a few tulips you grab at the market and throw in a tumbler (or cocktail shaker, or pitcher, etc.) will give an instantaneous lift to any home and to those within. Flowers are inherently life-affirming and restorative, magical amulets against gloom and sadness. It’s nearly impossible to mess up an arrangement of flowers, especially if you remember to cut off more of the stem than you might think to at first. All colors of flowers “go together.” And an arrangement of all white flowers is the freshest, cleanest thing in the world.

It’s interesting that Burroughs would single out the potential admiration of guests as the first reason to learn more advanced techniques of flower arranging; it’s fun to splash out on a big centerpiece when guests are coming, but my own love of flowers at home is mostly selfish. A vase full of irises in their lush, delicate tints cause a small leap of pleasure each time you walk in the room. (Plus the cats won’t shred them, the way they do roses.)

In any case, it turns out that Laura Lee Burroughs’ deceptively innocent observations were the fruit of a weirdly brilliant and disordered mind. She went far beyond producing improbable arrangements of flowers in lurid WWII Wizard-of-Oz Technicolor. Her little books are highly elegant, forward-thinking works of passion and imagination illustrative of the American love of Japanese minimalism that would go on to inform the mid-century, and also — however unintentionally — of the country’s growing vulnerability to corporate-sponsored materialism. Her style and message are, in fact, not entirely unlike those of her son, the novelist William S. Burroughs, author of the avant-garde masterpiece Naked Lunch. Each displayed a sort of perfect aesthetic pitch against a backdrop of panic and discomfort.

You could say that both writers were disturbed moralists, struggling to express a natural and beautiful view of the world within the stifling confines of American materialism and conformity.

For Laura Lee Burroughs’ three-volume flower arranging series was the bald promotional effort of the Coca-Cola Company. What today we would call “sponcon.” Page through and you will marvel as images of elaborate flower arrangements involving large Czech pottery birds, walls of bamboo and Chinese enamel vases are slowly invaded by bottles of Coca-Cola. By the end of Vol. 2, the flowers and porcelain have given way entirely to wooden buckets and carved pails of ice holding piles of curvaceous green glass bottles of Coke. (“Under a sheltering umbrella, two garden cronies discuss their Zinnias over bottles of ice-cold Coca-Cola.”) The idea of the series was to associate Coca-Cola with wholesome and refined homemaking; millions of Burroughs’ pamphlets were sold at 10 cents each during the war (cheap even then — little more than the cost of postage and handling, when you consider that a six-pack of bottled Cokes cost a quarter in 1941).

A photograph of the author herself appears in the third volume, published in 1943. She’s seated primly, wearing a long white tea gown and a slightly mutinous expression, holding a bottle of Coca-Cola: She’s the personification of all that is lovely, freakish and troubling about the American Dream. What order is here, what cleanliness! And what prescience. Julia S. Berrall published the standard History of Flower Arrangement 12 years later, in 1953, and there is very little in that book that advances beyond Burroughs’ notions of joining a Japanese spareness and line with a European sense of palette and profusion.

The irrational imperative of hauling Coca-Cola into the proceedings had an unfortunate effect on Burroughs’ prose, however, and, perhaps even on her state of mind.

“Flower arranging will give you an outlet for that artistic urge you long to use,” she promises her readers. “Start today; even a small effort will produce results. Your home will quickly reflect the beauty you have learned to express.” You needn’t worry, neophyte flower arranger, if your attempts fail at first: “If ideas elude you, don’t be discouraged; it is all a matter of study and practice. Pause and relax with ice-cold Coca-Cola. Eventually your success will be assured.”

Read this passage a few times and you will have to agree that what is being suggested is that drinking Coca-Cola will (“eventually”) enable you to arrange flowers: a primitive version of the demented marketingspeak to which we have all become so sadly accustomed.

William S. Burroughs spoke out against this particularly American form of madness many times, as he did in Naked Lunch, the infamous (and excellent) novel his mother nearly disinherited him over.

TECHNICIAN: “Now listen, I’ll say it again, and I’ll say it slow. ‘Yes.'” He nods. “And make with the smile… The smile.” He shows his false teeth in hideous parody of a toothpaste ad. “‘We like apple pie, and we like each other. It’s just as simple as that’—and make it sound simple, country simple… Look bovine, whyncha?”

I am kidding, a bit… it’s unfair to blame Coca-Cola alone for the bonkers condition of Laura Lee Burroughs. The Burroughs and Lee families both were as packed full of loons as a David Lynch movie. Both Laura and William had an unhealthy fascination with the “occult” — the family believed her to be psychic, and she went in for Ouija boards and visions of doom. As for William, he was into everything from Aleister Crowley to Scientology, at various points, and went around putting curses on people, and so on. It was no help whatsoever to the mental stability of the Burroughs clan when William accidentally shot and killed his wife Joan at a party in Mexico City in the fall of 1951, in a “William Tell routine” gone fantastically, horrifically wrong. Though that is a tale for another day.

William’s son Billy once wrote of his grandmother Laura, who largely raised him:

Laura was so ethereal she needed [her husband] Mote’s more solid realities to keep her relating to the world. She was much the stronger and brighter of the two, but when he died, she went promptly insane and in the slanting window light saw drunken gauchos playing cards and slicing into one another’s faces with broken bottles and knives.

Despite everything, though, it cannot be denied that in Laura Lee Burroughs’ books there are beautiful flowers and an overwhelmingly attractive sense of peace, tranquillity and order.

For me that is the lesson of these exotic and beautiful early (sponcon) works of art and design. Flowers are fragile, their beauty evanescent, but the sense of calm and of pleasure induced by a copper bowlful of Tritomas meticulously arranged on a needle holder is eternal. (“After several hours in water, they curve and tend to turn upward, candelabra fashion.”) Nothing can alter them.