Red-Lining Has Been Outlawed for Nearly 50 Years. How Come We Still Feel Its Impact?

For hundreds of years, it was legal—and even encouraged—to prevent Black people from owning homes. Banks and mortgage lenders could, with the assistance of the U.S. government, outright refuse to provide homeownership loans to Black families through a process known as red-lining. It wasn’t until the 1968 Fair Housing Act that the government banned the lending practice and called it for what it was: housing discrimination.

What is red-lining?

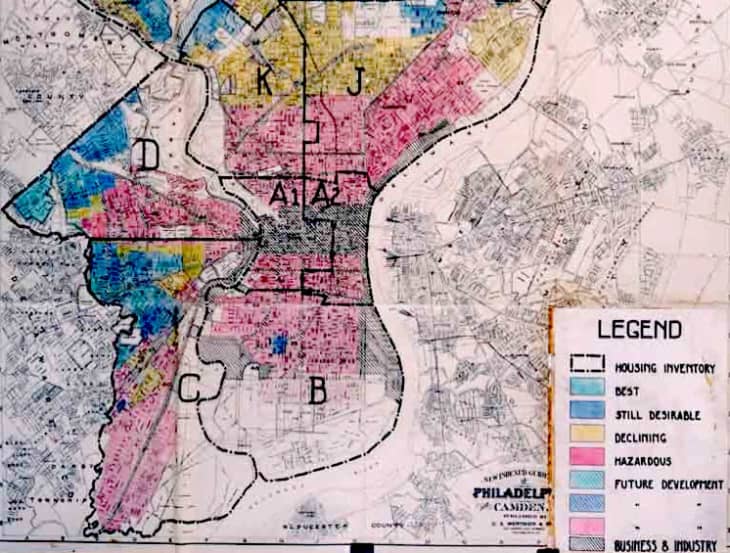

Despite what we now know about its harmful, long-lasting impacts, red-lining was initially backed by the federal government’s 1933 Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) as part of New Deal legislation. During the Great Depression, the government wanted to understand which houses were likely to default or be at risk of foreclosure, so assessors from the HOLC surveyed neighborhoods’ property values. Based on their findings, the HOLC drew boundaries around desirable and undesirable neighborhoods—neighborhoods with the worst ratings were colored red, hence “red-lining.” (Conversely, a “good” rating was green). Ultimately, white and wealthier neighborhoods got better ratings than poorer neighborhoods home to mostly people of color.

After soldiers from World War II returned, lenders consulted these maps—which were once used to assess potential loan payment liabilities—to offer desirable mortgages in well-ranked neighborhoods to white veterans and discriminate against Black veterans and veterans of color. Mortgage lenders and financial firms intentionally turned away Black people with good credit. The discriminatory lending practices codified racism and set the stage for generations of racial wealth disparities.

What are the effects of red-lining?

Nearly 100 years since the start of the now-defunct Home Owners Loan Corporation and the attempt to counteract it in the Fair Housing Act, everything from public school funding to air quality to debt to police interactions are dictated by neighborhood wealth and access to resources. In refusing loans to Black homeowners, banks and other financial institutions addressed a problem that didn’t exist (the idea of run-down neighborhoods with little promise of property appreciation) and created new ones. Which is to say, current racial and economic disparities in quality of life, and personal and public health are rooted in lines drawn decades ago.

Jesus Hernandez, founder of consulting firm JCH Research and a former lecturer at the University of California, Davis, has studied the impact of red-lining on modern-day economic crises, including “linking the financial recession to historical practices of housing discrimination and predatory finance.” Hernandez says that his research has found a “connection between race and subprime lending for every census tract in the U.S.”

Subprime lending, when lenders knowingly provide loans to people who will have trouble paying them back, is a predatory lending practice that exploits a homeowner’s difficulty receiving a loan. In the 1990s, this sort of predatory lending contributed to a 43 percent increase in homeownership by Black families, a process that continued through and contributed to the 2008 Great Recession.

This production of inequality in housing opportunities reproduces itself in other ways. Formerly red-lined neighborhoods are more likely to be considered “food deserts,” where families suffer from decreased access to healthy food. Researchers have also tracked the connection between red-lined neighborhoods and green space, finding that wealthy neighborhoods had more trees and greater access to parks, resulting in greater mental health outcomes and fewer heat advisory days.

How did red-lining affect today’s property values?

More than the day-to-day life that is altered and shaped by decreased public investment in red-lined communities, houses in red-lined neighborhoods have increased 52 percent less in property value than whiter, wealthier homes. In most cities across the country, public education is determined by where a student lives, and funding for these schools is also contingent on property values. This means that housing values have a positive correlation with school performance, so much so that property values are $205,000 higher in well-scoring areas than in lower-scoring school neighborhoods.

For most families, a house is the single largest asset they own. A home is the marker of middle class attainment as well as a way to shore up familial generational wealth. It is also, as we’ve seen, an opportunity that Black and brown families have been boxed out of, one that continues to present and protract social and economic challenges.