Here’s When a Sears Kit House Is (and Isn’t) Worth Saving

The kit houses of the 20th century have an enthusiastic following. There are plenty of people who seek out Sears kit houses, wanting to own and restore their own part of history. To say they’re highly romanticized and sought-after would be an understatement.

But for the uninitiated, the phrase “kit house,” and the concept of all its parts arriving in the mail, can conjure images of hastily manufactured homes that aren’t built to last.

So, what’s closer to the truth? Were kit houses simply the suburban prefab houses of their generation, or are they a historical treasure worth saving? Here’s what four historic preservation, architecture, and real estate experts had to say.

What is a “kit house”?

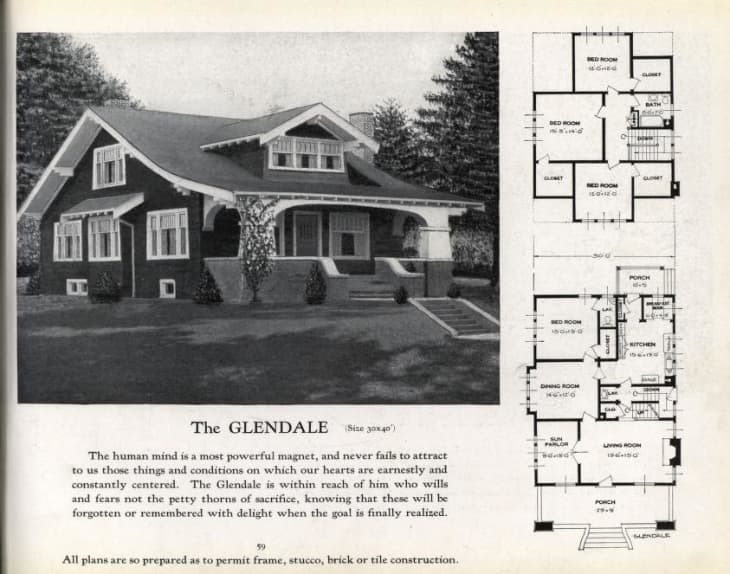

“Kit houses came on the scene in the first decade of the 20th century and were sold in catalogs by popular mail-order companies such as Sears-Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and other companies like Aladdin Homes,” says Christina Dikas, associate principal at Page & Turnbull, an architecture and historic preservation firm. These homes coincided with a boom in suburban building, particularly with the rise of streetcar suburbs and a move toward more single-family constructions.

“They aligned with the industrialization and standardization of the construction industry,” explains Dikas, noting that the styles could range from Tudor Revival to Cape Cod to Four Squares to Colonial — far broader than the Craftsman bungalow houses often associated with this era in building.

She notes that while they were modest in size, Sears kit houses had decorative details you wouldn’t see in a prefabricated home today. “They featured decorative trims on the exterior and interior, hardwood floors, built-in shelves, cabinets, and even stained glass windows that were manufactured en masse and available to the general public,” Dikas says.

Stacy Grinsfelder writes about her own restoration work at Blake Hill House and hosts a podcast called True Tales from Old Houses. “Some homeowners were building these homes themselves, others hired contractors who specifically built kit homes — think of them as the people that put your IKEA furniture together today,” Grinsfelder says. “They specialized in following plans.”

How do I know if a kit house is worth saving?

Author, researcher, and lecturer Rebecca Hunter is a kit house expert who explains that kit houses, which are also known as mail-order homes, represent an important pillar of American architecture from 1906 to 1982. “Since mail-order homes were rare, and the USA is the only country that produced them on a national basis, they are historically important,” she explains.

According to Hunter and other historians, if you have a Sears kit or mail-order home, it is nearly always worth saving. However, they are often confused with “plan book homes,” which sent only plans and a list of materials. They’re also confused with prefabricated and panelized or sectional homes, which were typically manufactured with cheaper materials and shipped in sections to a building site.

“Meanwhile, kit and mail-order homes were ordered from a company catalog, consisting of top quality building materials and plans, with or without pre-cut framing boards,” explains Hunter.” [They were] assembled by a carpenter just as a non-mail order home would be.”

In other words, kit houses were quality.

“Today, prefabricated houses often use composite-type materials that look good initially, but aren’t meant to last. The mid-century kit houses used real wood on their trim, but now it’s often composite fiber material,” adds Jason McCree Gentry, a global real estate advisor with Sotheby’s.

The phrase “built to last” comes to mind for architecture experts.

“These homes were not similar to the tract homes of today. The wood and building methods were similar to most houses of that time, and houses then were built to last,” says Grinsfelder. While the condition of a kit home is often a wildcard depending on whose hands the home passed through over the decades, they’ve generally stood the test of time.

Is there ever a case for demolishing a kit house?

There are, of course, some houses that are beyond repair. If a house has been neglected for decades to the point that it is falling in on itself, demolition may be the only solution. But this should be the rare exception, according to the experts.

Gentry notes that it matters who the caretakers have been during the course of its life. “Did they maintain that home well? Did they update and upgrade with current technology?” he asks. “These factors will vary greatly between the homes and might decide if a home can be saved.”

But because of their historical significance, Hunter says, “If an authenticated mail-order house must be demolished, I recommend photo and/or video documentation, so that we know what we have lost.”

How do you know if you live in a kit home?

It might be surprising to hear there’s no clear indicator that you own a kit home — unless you start opening up walls or you come across specific documentation. “In over 20 years of research on mail-order homes, I have found that approximately 50 percent of the people who do live in one had no idea, and 50 percent of people who think they have one actually don’t,” Hunter says.

If your goal is to take on the challenge of restoring a kit home, then it’s critical to find documentation or authentication. That could mean part numbers, shipping labels, mortgage records, blueprints, or correspondence from a mail-order company.

Why do kit houses matter, anyway?

Gentry explains that kit houses were built with simplicity and efficient use of space, storage, and cross-ventilation in mind. “These homes were built during a time period that represented a need for affordability and efficiency,” he says. They represented housing accessibility for the middle class.

Gentry continues, “They are a time capsule in the way of the ideologies, methodologies, and materials of that generation.” And, he adds, many people find the character and design of these homes charming.

“We find a lot of these homes in some of the most beloved neighborhoods in Charlotte, like Dilworth and Plaza Midwood,” says Gentry, who works in North Carolina. “They’re loved for their charm, character, and intimate scale, but many are getting replaced today with what some refer to as McMansions that do not relate at all to the context of their neighboring homes.”

Gentry muses whether the suburbs of today will carry the same nostalgia of kit houses — and whether there will someday be a case for their preservation. “If we fast forward 120 years from now, will we be so eager to preserve the suburbia explosion of today? People latch on to preserving communities, and we naturally crave nostalgia, especially when rooted in the authenticity of that era.”